The garment manufacturing industry in many low-income countries is characterized by minimum wages as decided by their respective governments and has a labor force with an overwhelming majority of women (Kabeer and Mahmud, 2004). However, despite the regularity of pay (monthly or bimonthly), many struggle to make their incomes stretch until the next payday (Breza et al., 2017). We conducted an exploratory study in a garment factory in Bangalore, a metropolis in south India to understand the short-term consumption smoothing problems (from one paycheck to the next) faced by a sample of 60 women workers. The interviews were conducted within the factory premises in an isolated room ensuring the privacy of respondents. The average age of the women interviewed was around 34 years; 82% were currently married while 18% were divorced/separated/widowed. The survey questionnaire was designed by Good Business Lab and Busara Center for Behavior Economics.

Living paycheck to paycheck

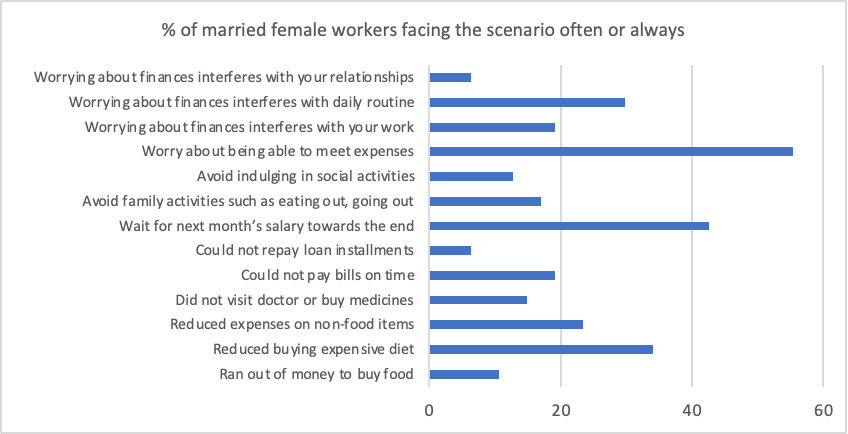

Nearly half of the workers surveyed said that they often or always worry about being able to manage monthly expenses and 40% find themselves waiting for the next paycheck towards the end of their paycycle (Figure 1). Their households had to cut down on medical expenses/doctor visits during illnesses (15%), miss timely payment of bills (20%), or reduce food and non-food expenditure in one-third and one-fourth of the cases respectively. About a third of them report that worrying about financial matters interferes with their daily routine while one in five reports that it affects their work lives too.

Figure 1: Percentage of married female workers facing high-stress scenarios

Financial stress among garment workers

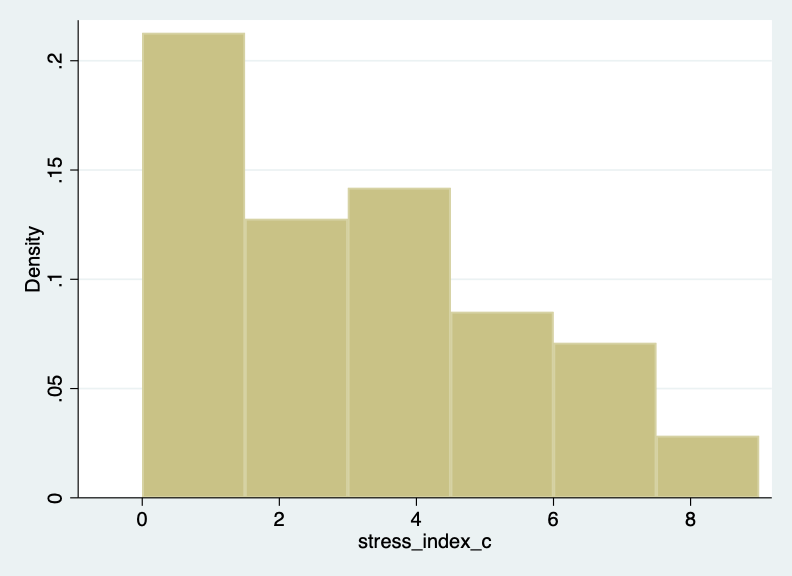

We construct a financial stress index as a simple count of the number of liquidity crunch scenarios that the workers reported facing as given in Figure 2. More than 50% of the women reported facing 4 or more liquidity crunch scenarios (often or always) in the six months prior to the survey out of the 13 presented to them. Additionally, married women who are primary earners had a higher stress index value compared to those women who report either their spouse only or both spouses as primary income earners. Thus, more than one-third of women workers surveyed live a hand-to-mouth existence from paycheck to paycheck. Further, ownership of assets like property, real estate, gold, and two-wheelers was associated with significantly lower stress index value.

Figure 2: Histogram of simple financial stress index

The inability to make ends meet over the course of a month is likely to have far-reaching negative consequences for the household as they continue to depend on expensive informal credit and face reduced ability to accumulate precautionary savings and cope with future income/expenditure shocks. When the workers were enquired about their ability to generate cash of INR 5000 (~USD 61) (equivalent to around half of a month’s wages) during emergency situations, two-thirds said they could raise such money in 30 days time whereas only 1 in 10 workers said they could raise this money in a week’s time. Around half of them reported having to rely on their extended family or other informal sources while only 1 in 4 reported that they can dip into their savings.

Our intervention: Flexi-salary

Financial products are typically designed to improve individuals’ or households’ welfare by helping them follow through on their intertemporal plans (Brune et al., 2017). We design one such workplace financial intervention, i.e., the provision of access to liquidity between paychecks through an employer salary advance at zero interest rate. The study will randomize women workers at an individual level, where the option of salary advancement through a digital platform will be provided to the treatment group. This platform will be installed on a tablet(s) available in the factory. In a practical sense, for a worker whose take-home salary is INR 10,000/month (~USD 123), if she checks on the 20th of the month, and she has worked for all the working days till that day, she will have earned a salary of INR 7,333 (~USD 90). She can then withdraw up to this amount, which is transferred directly to her bank account.

We aim to investigate the effects of flexible salary intervention on women’s and their households’ financial well-being, financial stress, and reliance on informal sources of borrowing. We further explore the linkages between her ability to access money when most required and enhancement in her household bargaining power as reflected in her household financial decision-making and spending on goods and services as preferred by her.

Have any questions or thoughts on the article? Write to us at info@goodbusinesslab.org.